The costs of college tuition have been escalating in recent years. When combining this with the mounting student loan debt, it is hardly surprising that one critical debate has been renewed: should college be free? This timely question is something that has spurred spirited discussion among policy experts, educators, and the general public – all stakeholders trying to identify the best way of funding higher education. This matter stretches beyond simple financial spreadsheets and well into the future of the United States. That being said, in the following article written by our college essay writer, we strive to present a well-researched perspective on the current conditions of higher education in the United States.

Why College Should Be Free: The Historical Context of Government-Funded Education

The origins of government-funded higher education in the United States date back to a time when agriculture and mechanical arts were considered essential to the country’s prosperity and self-reliance. In the mid-nineteenth century, the Morrill Land-Grant Acts laid a critical foundation for what would evolve into America’s extensive public university system. The first Morrill Act was passed in 1862. It set the tone for advanced learning becoming more widely available to average citizens. This contrasts with the classical education that was reserved for the elite, giving rise to a small amount of privileged educated citizens.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the federal government continued strengthening its ties to the universities. This was accomplished using numerous unique programs designed specifically for expanding educational access. Following World War II, for example, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944—commonly known as the GI Bill—helped hundreds of thousands of returning veterans attend college, many of whom were the first in their families to do so (“Servicemen’s Readjustment Act”). This nationwide effort dramatically increased college enrollments, propelled universities to grow in both size and prestige and underscored the role of public investment in shaping the nation’s academic landscape. In the decades that followed, legislation kept on promoting governmental support of higher learning. An example of such efforts was the establishment of the Pell Grants of the 1970s. They were named after Senator Claiborne Pell and represented a new commitment to helping low-income students. This would enable them to attend college with fewer financial barriers than before.

The institutions that reaped benefits rose with the evolution of government programs and policies. That is, public research universities, community colleges, and historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) all blossomed under the new framework. The key was in recognizing that a better-educated populace would bring forth collective benefits. However, federal aid and its scope shifted over time. This change reflected the political tides and economic pressures of each period. For example, during times of national prosperity, there were funding increases, while cutbacks took place during periods with tougher fiscal climates. In any case, what has been constant is a conversation that has spun over decades, examining to what extent it is right for governments to sponsor higher education.

Present-Day Costs and Tax Implications

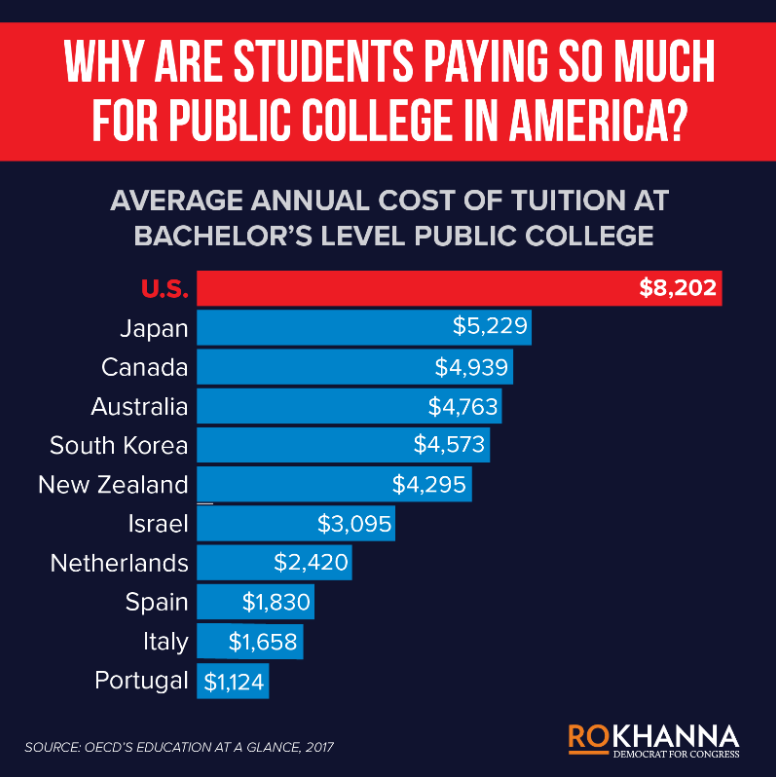

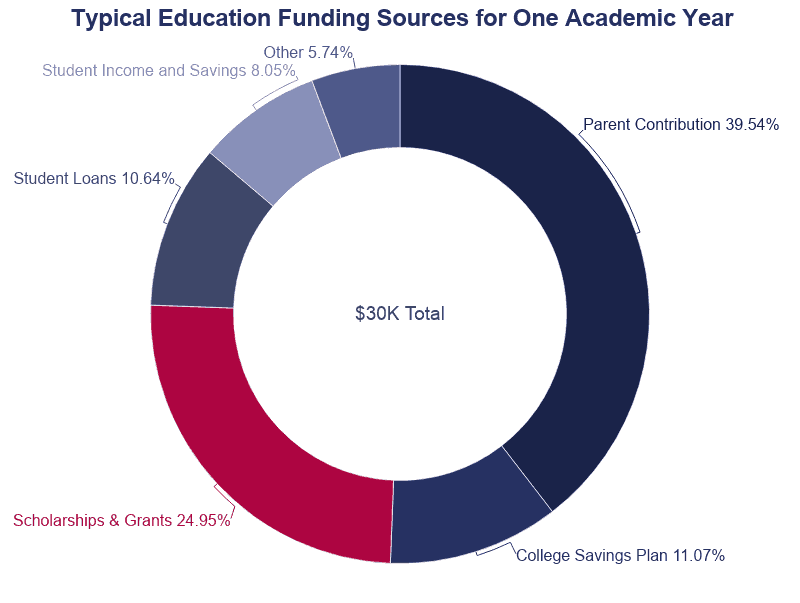

Undeniably, the costs of higher education continue to climb. Students and families across the entire United States keep grappling with a financial reality that is becoming gradually more complex. As recent Department of Education reports demonstrate, the average annual tuition for public institutions that offer four-year programs amounts to about $10,000 for in-state students (Hanson). When it comes to private, non-profit colleges, the costs can even be over $38,000 per year in tuition and fees alone (Hanson). The figures in question do not cover additional expenses such as room, board, textbooks, and other living costs in spite of the fact that they can push the total price for a four-year degree far higher.

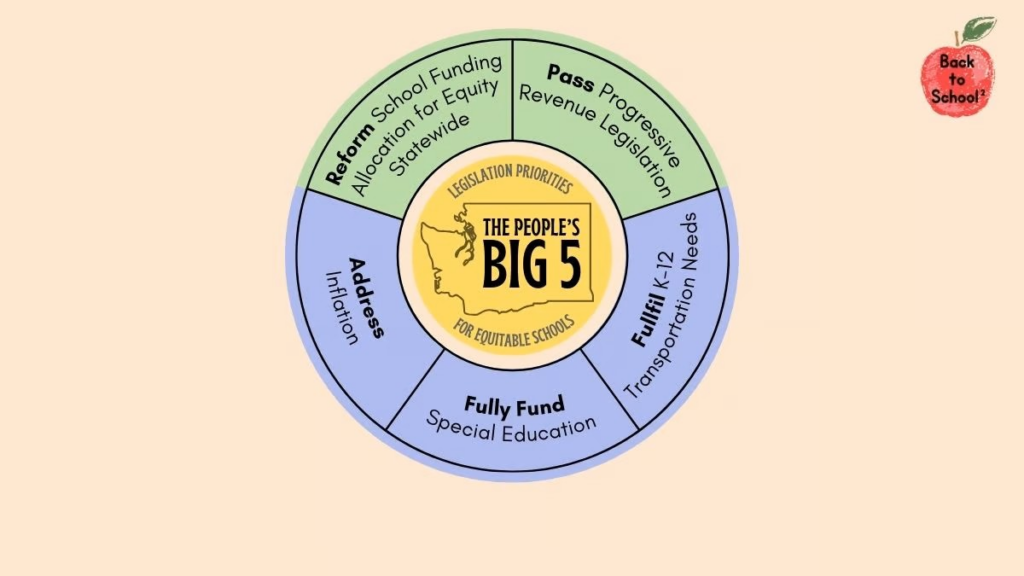

Examining this issue inevitably raises questions about how existing tax policies intersect with higher education funding. Government support of public universities is already substantial, often channeled through state appropriations that directly lower tuition rates compared to those at private institutions. Yet, states vary widely in how much they commit to higher education, creating stark regional disparities in the net price that students end up paying. In some states, underfunded public systems have led to rapid tuition hikes, which shift the cost of higher education onto individuals rather than distributing it across taxpayers as a whole. By contrast, a model that leans more heavily on government subsidies or explores a free-college option—whether fully or partially covered—would necessarily involve higher tax revenues or the reallocation of existing tax dollars. The logic behind such proposals rests on the notion that a better-educated populace bolsters workforce competitiveness, lowers unemployment, and reduces the need for certain public assistance programs, potentially saving money for society in the long term.

In this matter, the federal government is a critical player. Specifically, the government provides grants and subsidized loans that aim to assist students. One such example is the Pell Grant. Yet, both grants and loans – in and of themselves – fail to decrease the prices of tuition. Their contribution is merely helping people cope with the harmful structure that already exists. Simply put, they do not reduce the overall expense in any way.

The idea of funding a free, or at least almost free, college system can be concerning for some taxpayers. They might worry that their tax burden may rise and, consequently, wonder if this approach is fair: Why is it that everybody should pay for programs that only a part of the population might make use of? Still, though, the advocates of the tuition-free approach counter this argument by saying that, ultimately, doing so would bring benefits to the nation as a whole. It would create a more broadly skilled range of workers and a setting that is more conducive to innovation and economic growth. Clearly, then, there is great tension when trying to untangle the matter of whether college should be free. The answer to this complex question lies in a solution that is cost-effective and equitable for all Americans.

Student Loans and Debt Analysis

In today’s American higher education landscape, few issues stir as much debate as the growing student loan debt crisis. This is understandable when we consider data from entities such as the Pew Research Center. To be specific, the statistics are alarming, presenting the case that the cumulative student loan debt in the United States has surpassed $1.6 trillion (Fry and Cilluffo). More than 40 million borrowers owe this startling amount, which only points to how widespread this problem is (Hanson). Indeed, for a significant portion of these debtors, fulfilling loan obligations means years—even decades—of monthly payments that can constrain career choices, delay major life milestones like purchasing a home, and ultimately shrink opportunities for social mobility.

Besides these more general figures, the situation has disproportionate impacts. More precisely, there is an uneven distribution of student debt among different demographics . For instance, while many traditional undergraduates may benefit from family resources or institutional scholarships, older students returning to college with established financial obligations—such as dependents or mortgages—can find the added pressure of student loans particularly burdensome. In that sense, when we wonder, “Should college education be free?”, we must connect the answer to wider equity and higher education access issues. In other words, this is not just an economic issue but also a social one.

If, in response to these realities, a model emerges wherein college is fully or partially subsidized, it might provide tangible relief for future generations by limiting or eliminating the need for student borrowing altogether. Yet that possibility raises additional questions about funding streams, the role of taxpayers, and which educational institutions would qualify. Nevertheless, for those already in the shadow of heavy student debt and spending money on an essay writing service, proposals related to whether college should be free nonetheless offer a glimmer of hope that the system could shift toward an arrangement wherein educational opportunities do not come with life-altering financial burdens. It is precisely the depth and breadth of these debts—and the human stories behind them—that help drive the debate, highlighting the urgency of forging sustainable, equitable solutions.

The Broader Impact of Free College on Society

The idea that higher education should become tuition-free, either partially or entirely, does not only shape the future of college campuses; it also affects matters pertaining to economic growth, social mobility, and even public health. Namely, when one asks “Should college education be free?”, the core of the question demands wider considerations. This means assessing the manner in which newfound access to advanced knowledge and skills has the potential to transform not only the lives of individuals but also the broader societal direction. In that sense, among the main arguments favoring college being free is the opportunity for the workforce to become more highly educated. This can spur further technological innovation and boost the competitiveness of our nation. As a matter of fact, a number of economic models suggest that once the proportion of the population with post-secondary credentials increases, research and development thrive. Start-up ventures proliferate too, which creates an environment that more readily translates ideas into practical applications.

Beyond macroeconomic considerations, free college can also reduce income inequality. By eliminating, or at least easing, the cost barrier to obtaining a degree, underrepresented groups may find new avenues for upward social mobility. Whereas large swaths of the population currently opt out of attending college due to financial constraints, a more inclusive system could open the door to positions in growth sectors like technology, healthcare, and engineering. This expanded access could have a domino effect on family income levels, intergenerational wealth, and educational aspirations among children in households where college was once deemed unattainable. In effect, measures that address whether college should be free can also chip away at structural inequities, helping to create a more egalitarian society.

Moreover, some proponents argue that free or reduced tuition can have tangible benefits for other public sectors, including healthcare. Studies consistently link higher educational attainment with better health outcomes, suggesting that college graduates are more likely to secure employment with robust health insurance, adopt healthier lifestyles, and utilize preventive care services (Lawrence). Over time, these factors can result in a healthier population, lowering certain healthcare costs and potentially reducing the strain on public health programs. Likewise, the labor market could benefit from a workforce more adept at adapting to shifts in technological demands. Employees who might previously have limited their skill development due to the costs involved could instead pursue continuing education or advanced certifications, making them more versatile and resilient in a dynamic economy.

Existing initiatives at the state and local levels help illustrate these concepts in practice. For example, several states now offer free community college programs for eligible students, covering tuition for the first two years. Tennessee’s “Tennessee Promise” program, launched in 2014, provides qualified high school graduates with the opportunity to attend community or technical college tuition-free, provided they fulfill mentorship and community service requirements. Preliminary data from these programs indicate that not only are college enrollment rates up among lower-income students, but community college completion rates are slightly improving as well. Though these results are still emerging, they offer real-world evidence of what happens when financial barriers recede: students who might otherwise forgo higher education due to costs can pursue credentials that prepare them for middle- and high-skill occupations.

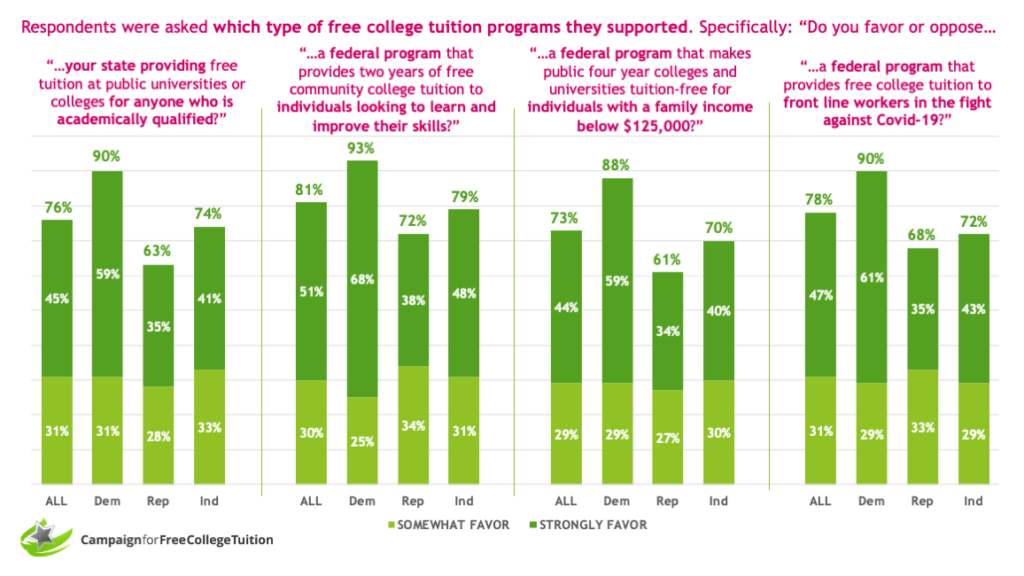

Public sentiment concerning whether college should be free appears to be evolving, with many polls suggesting widespread support for at least some level of tuition relief. While support levels can vary by political affiliation, age group, or region, the mere fact that this question garners extensive debate signals shifting attitudes toward the role of education in everyday life. In certain communities, proposals range from fully subsidized tuition for all in-state students at public universities to income-based arrangements wherein costs scale according to family resources. The common thread is the belief that removing financial barriers could unleash a collective benefit—more informed citizens, reduced reliance on social welfare programs, and a stronger economic foundation.

Counterarguments and Comparative Analysis

Proponents of tuition-free higher education often paint a picture of an enlightened society that reaps economic and social rewards from broad-based academic attainment. However, a full appreciation of the question whether college should be free requires engaging with the concerns and objections raised by experts and policymakers who question the viability and prudence of eliminating tuition. Moreover, this issue is often listed among the most popular persuasive speech topics for college students, highlighting its relevance. One frequently cited argument revolves around quality control: Critics contend that when institutions rely heavily—or entirely—on public coffers, they may have fewer incentives to maintain competitive standards, upgrade facilities, or attract high-caliber faculty.

Concerns about funding constraints also surface in debates about whether college should be free, as implementing broad-based tuition subsidies would likely require either raising taxes or reallocating limited government resources. Detractors argue that enlarging public spending for higher education could siphon money away from other critical social services, including healthcare, infrastructure, and K–12 schooling. This viewpoint emphasizes that every public dollar spent has an opportunity cost and that guaranteeing free college would weigh on taxpayers, particularly if the federal government steps in to bear the lion’s share of the expenses. In this sense, questions arise about whether it is fair to compel individuals—who may choose not to pursue higher education themselves or who may have already financed their own college degrees—to shoulder the costs of educating others.

It is not uncommon for policymakers to point out, with no small degree of disquiet, that a tuition-free scheme might prompt the state to impose further regulations—some possibly touching upon the very essence of university life, such as curricula, admissions standards, and systems of governance. While these anxieties do not, in every instance, determine the final verdict on a free-college proposal, they do serve to illuminate the complexities attendant upon any enlargement of the state’s role in funding educational endeavors. As is often the case in matters where public authority and private judgment intersect, the question of how to preserve institutional distinction while attending to society’s most pressing demands remains ever the subject of impassioned inquiry.

These apprehensions can be adequately evaluated if we use the lens of comparing the higher education model of the U.S. with the systems of Germany, Norway, and other nations. For example, the majority of undergraduate programs at public universities charge neither domestic nor international students with tuition. The German model is known to thrive precisely because this country continues to heavily invest in both vocational education and apprenticeships. This approach alleviates university pressures to enroll all interested students. In turn, this approach has led to relatively low rates of unemployment and a workforce that is technically skilled. At the same time, it is important to mention that the approach relies on robust governmental budgets, along with a social consensus that puts the greatest priority on education funding. Norway similarly provides free college for its citizens, though the nation’s smaller population, larger sovereign wealth funds, and comparatively high tax rates differentiate it from the American context. Norwegians are known for the tendency to accept more extensive public spending, following the reasoning that universal education brings benefits that notably outweigh the costs. Despite these apparent successes, critics stress that U.S. policies cannot merely replicate European models, given America’s significantly larger and more diverse population, its layered federalist system of government, and its differing attitudes toward taxation.

There is a stark difference in average student loan debt between the United States and nations offering free or heavily subsidized tuition. While Americans often graduate with tens of thousands of dollars in debt, many German and Norwegian students leave university with little to no financial burden. In practical terms, this means that about one-quarter of all Americans under the age of forty carry student loan debt, and the typical borrower owes somewhere in the range of $20,000 to $25,000 (Fry and Cilluffo). Such a side-by-side comparison would illustrate how national policy decisions regarding tuition charges, levels of public funding, and societal values about higher education shape individual financial outcomes. Yet even these successful examples exhibit trade-offs: High tax rates, constrained university capacity, and fewer private institutions are among the structural factors that delineate the European approach. Consequently, the debate over whether college should be free in the United States hinges on reconciling the potential advantages of open access with the challenges presented by broader funding, governance, and cultural norms. By acknowledging these differing perspectives, readers gain a more nuanced understanding that there is no universal model guaranteeing free college success; rather, the path forward calls for careful balancing of fiscal responsibility, academic quality, and equitable access for all.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The statistical evidence detailing rising tuition rates and ballooning student loan debt points to deep-seated financial strains, while debates over taxation and public spending reveal that funding higher education encompasses far more than balancing budgets. The societal ramifications—ranging from workforce development to health outcomes—suggest that policy decisions in this realm can reverberate throughout the entire fabric of American life. These findings affirm that access to affordable education has been a cornerstone in shaping the United States’ competitive edge, especially when considering historical government initiatives such as the Morrill Land-Grant Acts and the creation of Pell Grants. While it might foster a more inclusive and economically dynamic society, its potential costs and implementation hurdles—tax burdens, institutional autonomy, and governmental oversight—cannot be disregarded.

From a policy perspective, addressing the fundamental question of college being free calls for creative, evidence-based solutions that recognize the vast diversity of institutional missions and student needs. Policymakers might explore hybrid arrangements in which certain degrees or certificate programs in high-demand fields receive subsidized tuition, while other programs maintain partial tuition based on projected market outcomes. Additionally, strengthening existing financial aid programs could offer a pragmatic first step, perhaps through more generous grants, income-based repayment structures that truly reflect graduates’ earning capacities, or performance-based funding models that reward institutions for improving graduation and employment rates.

In sum, as this exploration has demonstrated, the question of whether college should be free is far from a purely theoretical exercise. It touches upon fiscal policy, social justice, workforce readiness, and the long-term health of American democracy. Ultimately, whether free college becomes a reality or remains an aspirational goal, the vigorous discussion it inspires will be crucial for shaping the trajectory of higher education—and, by extension, the future of the United States.

Works Cited

Fry, Richard, and Cilluffo, Anthony. 5 facts about student loans. Pew Research Center, 18 Sept. 2024, www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/09/18/5-facts-about-student-loans/. Accessed 16 Jan. 2025.

Hanson, Melanie. Average Cost of College & Tuition. Education Data Initiative, 26 Dec. 2024, educationdata.org/average-cost-of-college. Accessed 16 Jan. 2025.

Lawrence, Elizabeth M. “Why Do College Graduates Behave More Healthfully than Those Who Are Less Educated?.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior vol. 58,3 (2017): 291-306. doi:10.1177/0022146517715671Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (1944). National Archives, 3 May 2022, www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/servicemens-readjustment-act. Accessed 16 Jan. 2025.